Inventory of War Remains

Atlantique-Manche Regions

January 1, 2008 – December 31, 2013

Special D-Day Commemoration

June 2014

Sommaire

Introduction

Weapons in the inventory

Sanitary and environmental risk

Inventory of War Remains from January 1, 2008 to December 31, 2013 with maps:

Summary map

Normandy Region

Bretagne Region

Pays-de-la-Loire Region

Poitou-Charentes Region

Aquitaine

France, seriously injured by war

The result of 6 years of observation and analysis in 6 regions of western France is convincing. One day, the countries were at war and at the end, they didn’t leave. There is no armistice for war remains. In 6 years in the 6 targeted regions by Robin des Bois’s new inventory, 95,000 people were evacuated from their homes, workplaces, vacation spots, or schools because of bombs, mines, grenades, and shells that have been abandoned. From nurseries to retirement homes, evacuation is intergenerational. In 6 years, almost 14,000 weapons, dangerous to the population and for the environment, were discovered in fields, cities, the ocean, and freshwater. In 6 years, there was one death and five injuries. A century after the war of 1914-18 and 70 years after the war 1939-45, there are 62 underwater dumping sites for explosive weapons, called conventional weapons, and chemical weapons off the coasts of the Channel and the Atlantic, from Upper Normandy to Aquitaine. A century and 70 years after the two conflicts that destroyed and distorted the architecture and geology of France, there are 2 landfill and metal recovery sites and 1 freshwater disposal site for weapons in the regions Pays-de-la-Loire and Poitou-Charentes that pose grave problems to physical and environmental safety. Evidence of the mismanagement of the afterwar period may be found in the shells and grenades that are disposed of by citizens in the metal bins and the general waste bins of waste sorting and recycling centers.

600,000 tons of bombs were dropped on 1,700 French towns between June 1940 and May 1945. The majority were in cities. 15% of the bombs didn’t explode – fortunately – but the majority were buried 4 meters deep in soil and sediment, 6 meters deep for 20% of them, 7 meters for 10%, and 9 meters for 1%. The depth depended on the size of the bomb, the height of the drop, and the geological substratum.

The physical risks are violent. Old weapons can be set off in the public or private domain, maiming and killing if they are not handled by professionals, the bomb-disposal experts for Civil Security. After 70 to 100 years of vibrations, expansion, and deformation of internal clocks, they can explode. Laypersons should not touch them – none other than the bomb squad knows how to handle them.

On Omaha Beach, American geologists found in a sample of sand collected in 1998 that it contained micro-slivers of metal, 0.06 to 1 mm. 4% of the sand on the beaches was modified by the war.

Metallic shards in the sand at Omaha Beach © The Sedimentary Record

After the war came to the beaches, the Allied troops brought the war inland to the groves of Normandy. Today, forest, brush, and compostable waste fires are formidable. If the bombs and shells, separated or assembled, get caught in the flames, they will explode, making the fire worse and putting firefighters and civilians in danger.

Weapon remains become more toxic over time through alteration and corrosion. They release toxic substances into the environment. Forgotten shells are also environmental and sanitary time bombs. Mercury and lead are usually what initiates explosions. The secondary explosions free soluble, toxic compounds, prohibited above certain levels in drinking water. The bullets are hardened by arsenic and antimony. Systematic research must be undertaken in groundwater tables where soil was bombed, as well as sites where ammunition was collected and destroyed. The war leaves a trail that is anxiety-inducing, toxic, carcinogenic, and reprotoxic.

When they are judged non-transportable, war waste is destroyed on site without a assessment of soil or atmospheric pollution impacts. After the neutralization on site of the trigger by the bomb squad, bombs with their explosive charges, weighing dozens of kilos, are transported on the road to military camps for destruction. The bombs discovered in Normandy are transported to the military camp at Suippes, about 500 km away. Accidents on the road are not allowed.

Underwater weapons waste is out of all control. Some of them that aren’t buried too deeply will be found on the coasts thanks to the effects of storms and strong tides. Bombs, mines, and shells exploding in the ocean are dangerous for marine life – the acoustic effects, as well as those from the blast of air, can kill, maim, and disorient marine mammals and fish. A September 2010 directive on the safety of underwater explosion sites imposed specific provisions to protect marine life “as much as possible.” Under this instruction, the voluntary explosions must avoid fish-filled waters, the paths of migratory species, and areas of strong marine biodiversity.

According to the Environmental Code, citizens have a right to know what major risks they may be subject to. Yet, only the administrative offices of the Channel and Calvados release their “Departmental File on Major Risks” (le Dossier Départemental sur les Risques Majeurs, ou DDRM) – preventative information on the dangers of explosion and poisoning from unexploded ordinance (UXOs). Information is lacking and risky behaviors are increasing on beaches, on work sites, and in fields.

Weapons in the inventory

LANDMINES

War devices where the explosion is controlled from a distance or caused by the passing of a person, vehicle, or boat.

Anti-personnel landmines will explode at contact with a person or at their approach.

Anti-tank landmines are meant to destroy armored vehicles.

German-made ground mines: the “Luftminen” type

LMA (Luftminen type A): 500 kg / 2.10 m long / 300 kg of explosives

LMB (Luftminen type B): 1 ton / 3 m long / 700 kg of explosives.

These mines were dropped by plane with a parachute or laid by boats. They can be equipped with anti-disassembly and anti-recovery devices. They are very sensitive and fire could trigger at least a variation in water pressure.

BOMBS

Hollow metal projectiles, charged with explosive or incendiary materials and equipped with a device to start a fire, that used to be launched by canons and that are now largely dropped by planes.

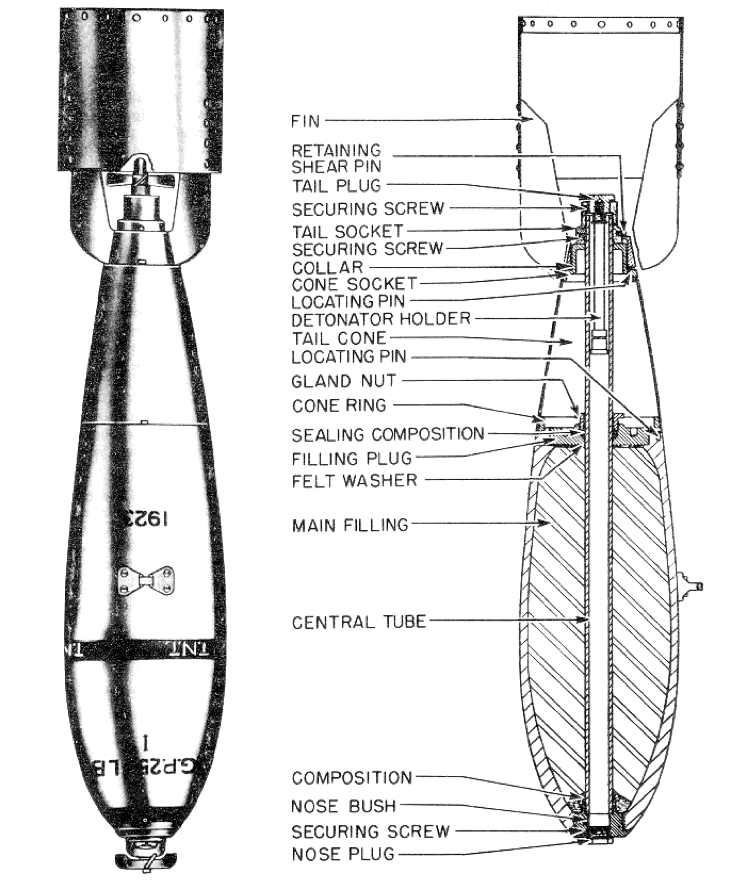

English bomb GP 250 (General Purpose)

From 104 to 113.4 kg / between 137 and 142 cm long

GP bombs were meant to break apart; after the explosion, they broke and the shards went flying. The GP 250 weighs 250 pounds (113.4 kg), of which half is explosive material.

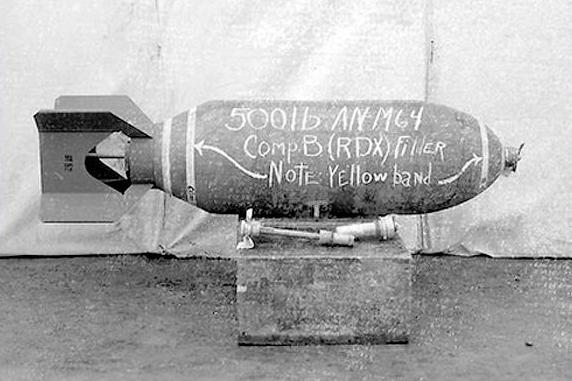

American bomb AN-M64 (General Purpose)

500 pounds (226 kg) / 145 cm long / explosive charge of 119 to 124 kg

It was dropped on railway bridges, docks, warships…

The yellow bands mark the body of the bomb © US Army

The yellow bands mark the body of the bomb © US Army

German bombs

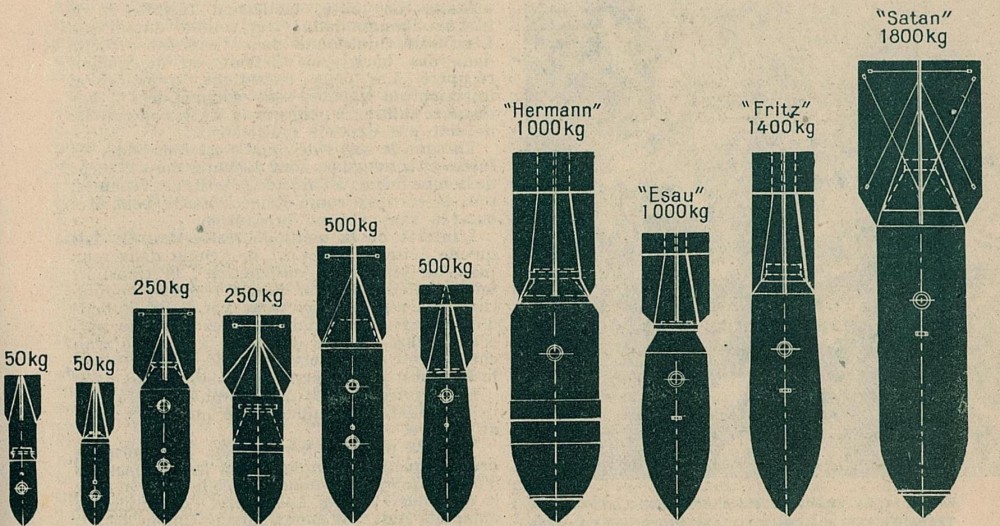

Below are the different types of bombs commonly dropped by the German Air force. They were drawn to scale, the smallest being about 72 cm long and the largest being 2.63 m (without the tailplane). Some had thin walls, others thick – the latter being recognizable by their smaller dimensions for an equal weight. The white circles indicate the placement of the rocket.

“The destruction of non-exploded bombs” C. Rousseaux. Science et Vie n°356. May 1947.

German SD bombs (Sprengbombe Dickwändig / thick walled)

One of the three types of standard bombs used by the Luftwaffe. These bombs were semi-perforated.

Ranging in size from SD 1 (17 cm / 0.76 kg) to the SD 1700 (3.3 m / 1.7 tons). They could be fragmentation bombs or anti-personnel bombs.

|

SD10 fragmentation bomb :

10 kg / 54 cm long / explosive charge 0.9 kg . It can penetrate concrete. |

Yugoslavian Stankovitch bomb

From 2 to 200 kg.

They were produced in present-day Serbia in factories in Smederevo and Krusevac. Smederevo exported its production to France. The principal warehouse was in Kraljevo. The Germans took possession of it and destroyed the majority of the bombs. It is rare to find unexploded Stankovitch bombs because they are particularly “reliable”.

SHELLS

A projectile shaped like a cylinder ending in a cone and that is equipped with an explosive charge. A shell can be shot by a mortar or a canon. There are many different sizes and weights.

Shrapnel shells

Shrapnel was invented during World War I by Englishman Henry Shrapnel. When it exploded in flight, the bullets would be projected in all different directions. It was abandoned for highly explosive shells, more effective for trench warfare. The name Shrapnel was eventually extended to other types of bullet shells.

Internal structure of French shrapnel © passioncompassion1418.com

American white phosphorus shells

American forces in particular used white phosphorus mortar shells, 81 to 107 mm long. The 107-mm shell weighed 11.57 kg and could be projected almost 4 km. Mortars could launch 15 shells per minute.

Incendiary shells made of white phosphorus were made to create chaos, to break positions, and to scare off the enemy. 20% of 81-mm American white phosphorus mortar shells were used at the beginning of the campaign of Normandy.

GRENADES

An explosive projectile that would be thrown by hand or shot by a rifle, made up of a metal cover holding a charge and equipped with a fire-starting device.

American white phosphorus grenades

White phosphorus grenades were incendiary and produced smoke screens that destabilized the enemy. There were two types in the American army – one by hand and one by rifle. They were nicknamed the Willie Peter (WP – white phosphorus).

American soldier in action with an M 19 A 1 phosphorus rifle grenade.

English Mills grenades

Created for World War I, these hand and rifle grenades were used during World War II and weren’t retired until 1970. Weighing 770 g, they were charged with explosives like Alumatol, Abelite, Cilferite, Amatol, or Bellite.

© http://militaryhistorynow.com

THE GERMAN COASTAL DEFENSE

German head of defense on the Atlantic coast, the Marshal Rommel placed obstacles designed to prevent landing, destroy equipment, and “annihilate the troops” of the Allies on the beaches and backshores. The measures counted among others the concrete defense blocks that contained landmines. They exploded upon contact with tanks, barges, and ships. The concrete cover over the landmine could also be tripped by large shells or other weapons.

Sanitary and environmental risks

Abandoned and degrading weapons produce 3 sources of pollution.

1 – Metallic pollutants

Zinc, cobalt, copper, tin, nickel, and aluminum were present in the hulls of bombs and shells.

Antimony and arsenic “hardened” bullets.

– The abnormal amount of zinc and copper in the groundwater in the south of Verdun was detected by the Office of Geological and Mineral Research (le Bureau de Recherches Géologiques et Minières – BRGM) in 1975. The only plausible origin that explains the levels of zinc and copper is the impregnation of the battlefield by the spray of exploding shells and the degradation of abandoned shells that weren’t fired and fired shells that didn’t explode into the soil.

– Omaha Beach is the D-Day beach, where the combat was the hardest and most intense. American geologists found small metallic shards, 0.06 to 1 mm, in a sand sample collected in 1998. 4% of the sand is polluted by metallic elements. On the dawn of D-Day, Omaha Beach fell under siege, with intense artillery shooting both on land and at sea between the German and Allied troops.

2 – Explosive residue

– Mercury fulminate and lead azide were used as primary explosives in shells, bombs, and grenades during the two world wars.

– Potassium and ammonium perchlorates that were used as explosives, particularly in English and German weapons, polluted the soils of the battlefields during World War I. For 3 years, perchlorate content has been detected in the north and east of France in drinking water. In the name of precaution, officials recommended that pregnant and breastfeeding women not drink the tap water and that parents do not prepare bottles with tap water for babies younger than 6 months. Perchlorates are suspected to have negative effects on the thyroid gland. They aren’t carcinogens. Thousands of towns are affected. The highest levels in the north – Pas-de-Calais, Picardy, and Champagne-Ardenne – are linked to the frontlines of trench warfare and with high density of ammunition discoveries that were mapped by Robin des Bois in the April 2003 inventories.

– TriNitroToluene, nitrobenzene, nitrophenol, nitroanisole, and nitronaphtalene are the principal explosives for conventional weapons used in the World Wars. They were byproducts during the deflagration and degradation of persistent, soluble, and undesirable toxic substances in water destined for human consumption – particularly organonitrate compounds, phenol compounds, and dinitrocresols used as herbicides and insecticides. The maximum amount allowed in drinking water is 0.1 mg/l.

In France and in Europe, the current state of aquatic resources as imposed by the Directive European Framework on inland and coastal waters does not take into account the risks of localized or diffused pollution caused by the endurance of abandoned ammunitions or their residue.

There’s no question that all the French regions that were subjected to bombings and artillery fire can still be, to this day, contaminated by the World Wars. However, the frontlines, intensively bombed areas, historic abandoned ammunitions dumps, and destruction camps should be, in our opinion and in the opinion of many experts on polluted sites, the object of an attentive and preventative study.

3 – Chemical ammunitions

Over time, chemical ammunitions have contaminated soil and groundwater. The “Place à Gaz,” 20 km from Verdun, has been contaminated by arsenic and the on-site burning of thousands of chemical weapons issued during World War I, echoing the Borcq-sur-Airvault site in the west of France contaminated by the on-site burial of chemical weapons during World War II.

The environmental effects of degradation or explosion of abandoned phosphorus ammunition used during World War I and II are ill known.

Inventory of War Remains from January 1, 2008 to December 31, 2013

only available in French

Imprimer cet article

Imprimer cet article